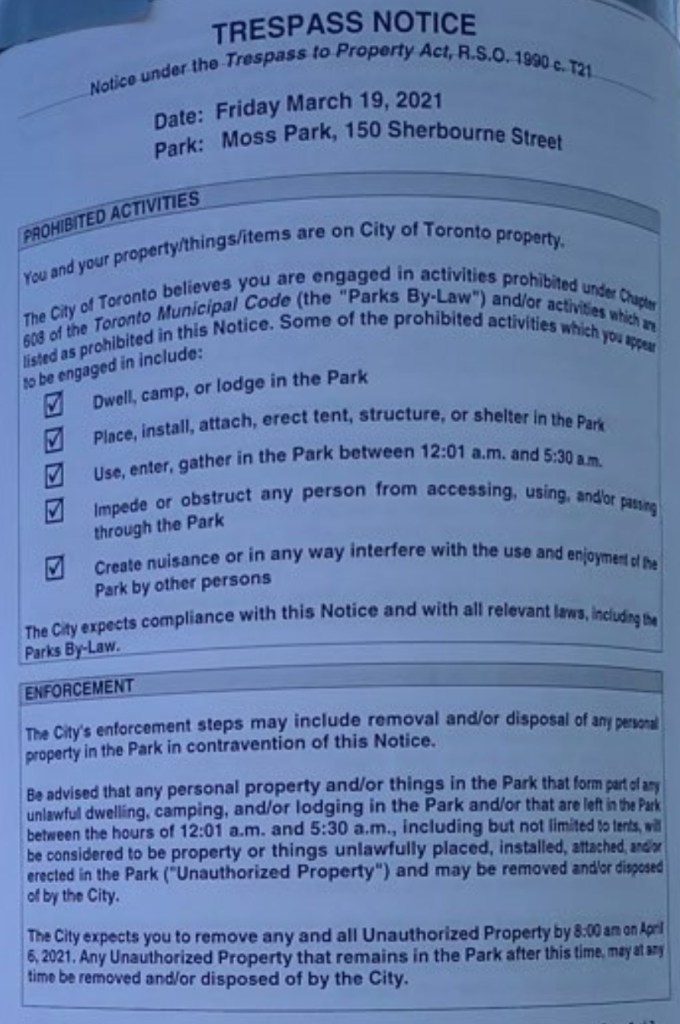

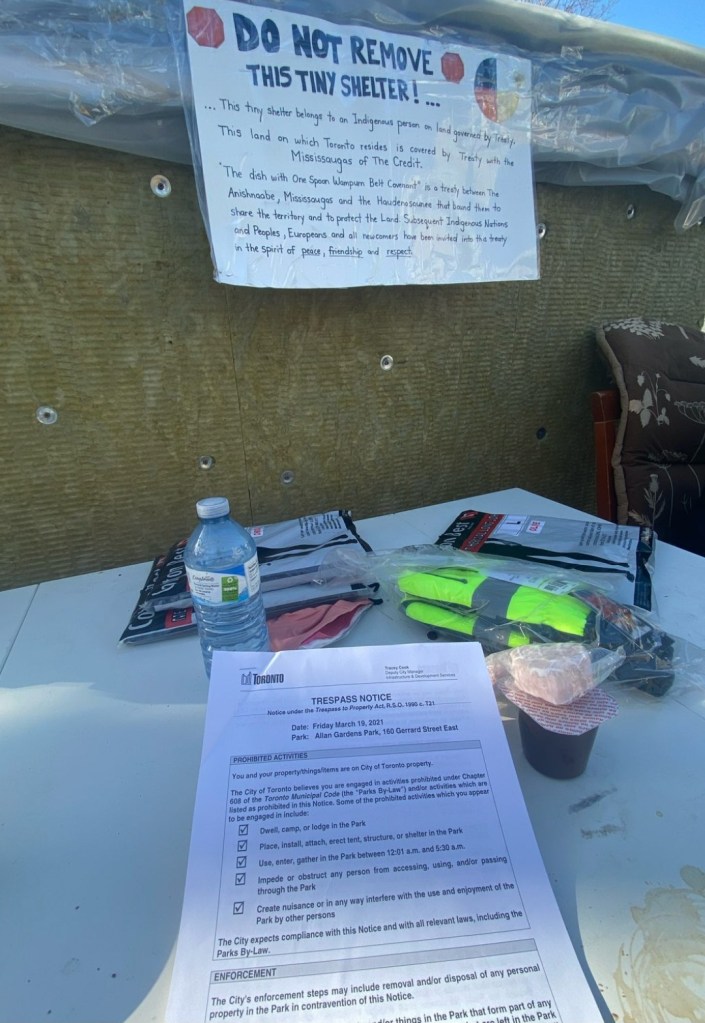

FACT: In 2021, The City of Toronto subjected unhoused Torontonians in City parks to intensive privacy-violating surveillance;1 planned complex multi-departmental operations involving hundreds of City staff, private security, and police to remove park users from parks and prevent their return;2 subjected Torontonians in parks to physical violence;3 and closed all access to large portions of several City parks for months with fencing and 24-7 security.4

Notes:

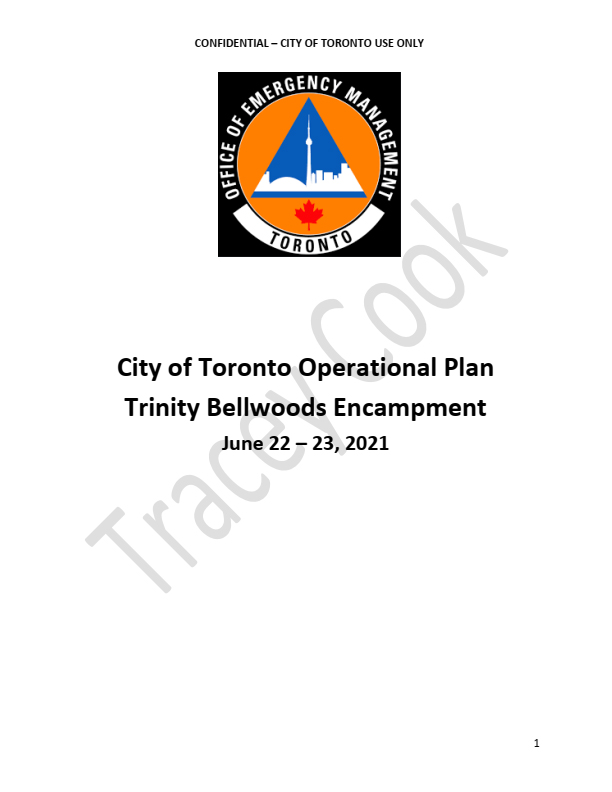

City Claim: City of Toronto. (2021, June 18). The City of Toronto continues to take significant action to assist and protect people experiencing homelessness and ensure the safety of the City’s shelter system.

- Source: Documents provided by the City of Toronto in response to a request to the City of Toronto under the Municipal Protection of Privacy and Freedom of Information Act for information regarding the Trinity Bellwoods Park eviction. The Operational Plan includes surveillance of residents – some of this information has been redacted by FactcheckToronto to protect residents’ privacy. Additional documents received through this FOI request demonstrate the extensive surveillance of encampment residents, but have not been included to protect residents’ privacy.

- Ibid.

- The City’s efforts to clear City parks at Lamport Stadium, Trinity Bellwoods Park, and Alexandra Park resulted in Toronto residents being physically assaulted and pepper sprayed by police. On October 25, 2021, 5 Torontonians filed a lawsuit against the City of Toronto, the Toronto Police Services Board and four officers for the injuries they suffered when the Lamport Stadium encampment was cleared, which included traumatic brain injuries, concussions, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Throughout 2021, following the eviction of people living in City park encampments, the City of Toronto has been fencing off large portions of those parks to make them inaccessible to all Toronto residents. This has been observed at George Hislop Park, Trinity Bellwoods Park, Alexandra Park, and the parks at Lamport Stadium. The fencing costs alone for Trinity Bellwoods Park, Alexandra Park, and Lamport Stadium totaled approximately $357,000.